Dreamers Without Borders

"Dreamers without Borders" is a binational education program designed to reconnect Dreamers, and US Citizens with Mexican origins who live in the United States, with Mexico. This is done through trips with agendas for educational, cultural and recreational events.

Because of the current situation all travel is on hold. We hope to resume as soon as possible.

Below you will find stories of Dreamers, written by Fernanda Caso. These stories are dreams in process. Each one of them is important and unique.

We published a document with recommendations to improve the DACA program. You can read it HERE

-

Having DACA to study regenerative medicine

By Fernanda Caso

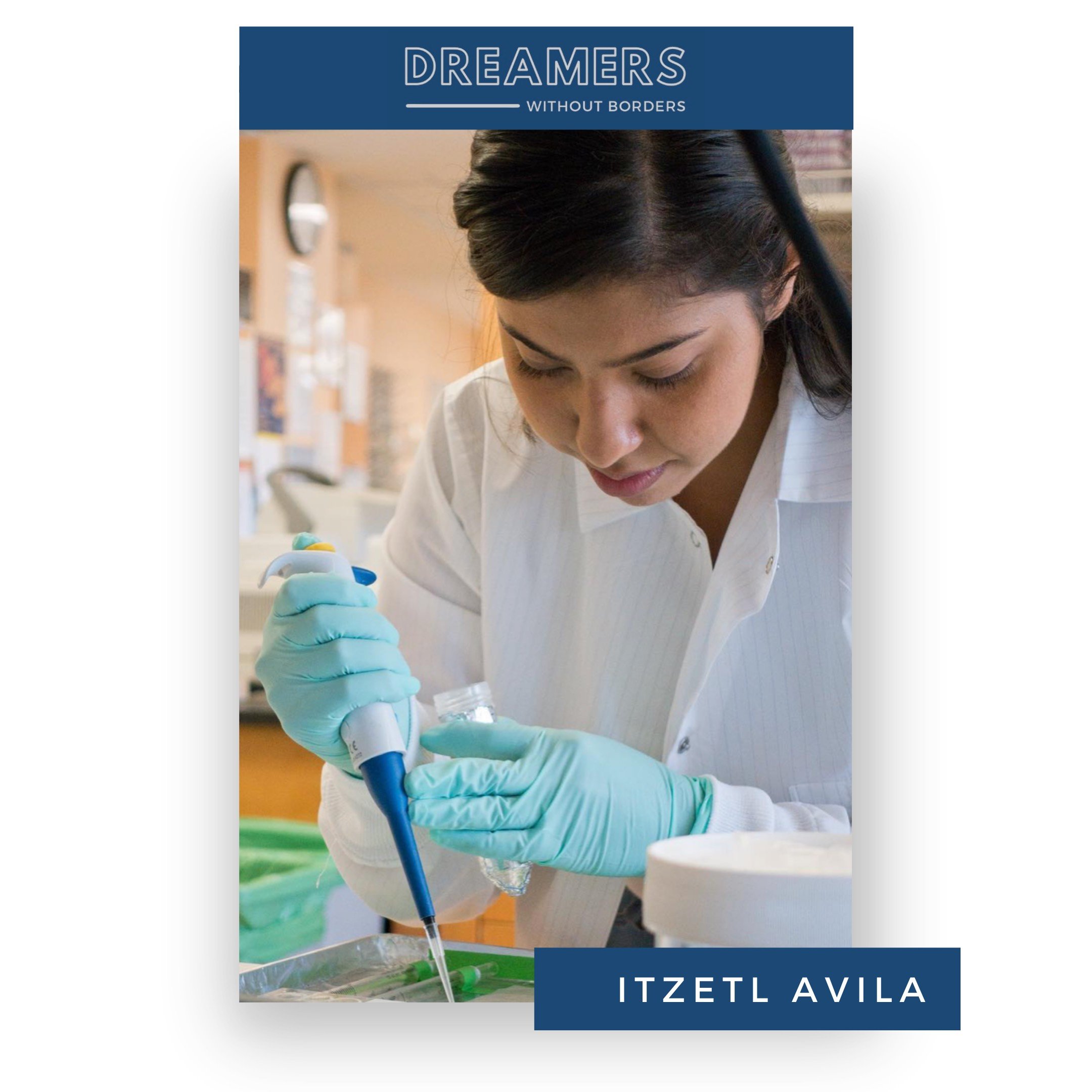

"My mother says that I cried all the way to the United States, but I don't remember the trip," says Itzetl, who was 4 years old at the time and crossed the border with her parents and three siblings. Today she is the administrator of a regenerative medicine laboratory at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

The Avilas settled in the San Fernando Valley, California and quickly integrated into the community. Her mother worked as an apartment manager and her father did repairs and maintenance in the complex. Itzetl was a student of excellence, always with honors and first place in her class.

Everything seemed to be going well until her father was deported for the first time. Due to a traffic stop, they took him before a judge and was deported because of his immigration status; his family did not see him again until two years later, Itzetl was in high school when this happened. The emotional loss was compounded by the economic crisis that was triggered by the deportation of her father. They were left with nothing, sometimes they didn't even have the money to buy enough food. Her father managed to return but was soon deported again, each time this happened, the economic situation worsened. Her mother made efforts to support her four children and her father suffered long periods of depression derived from not being able to be with them and help them.

Itzetl then decided to start working to help her family. She got a job selling clothes at a flea market, until she finished high school. Thanks to DACA and her qualifications, she entered the community college to study Biology, and later transferred to UCLA where she focused on cellular and molecular biology.

Along with her studies, Itzetl did intense social work. She collaborated as a volunteer at the University offering medical and social services to homeless people, helped in the intensive care unit in a hospital and participated as a mentor in the organization "Doctors, Nurses and Dentists for the People."

Even though she just graduated in June, Itzetl is already the administrator of the place where she once interned as a student. It is a laboratory at UCLA that has three areas of research: cancer, skin and brain. Although her specialty is skin cells, she is in charge of keeping everything in the lab working. This involves monitoring the growth of the culture cells and making sure all projects have the necessary inputs. Working in the laboratory allows her to continue doing research and focus on getting in medical school, which she hopes to apply within the next year. Her first academic article is in the revision phase, and getting ready to be published soon.

-

Having DACA to play tennis

By Fernanda Caso

Adrián, according to his father in a video circulating on YouTube, had a talent for playing professional tennis. That was his dream. However, to enroll in the high-level championships that would have allowed him to refine his technique, it was necessary to be a resident, and he did not have papers. Nor could he ever go to any international tournament because leaving the country meant not being able to return. Despite this reality, Adrián never let go of the racket, it was his passion and he practiced the sport intensely without knowing that it would open other doors in life.

His parents brought him and his brother to the United States in 1991, when he had just turned three years old. He found out that he was undocumented 9 years later, at 12, when his paternal grandfather became seriously ill and his parents had to explain to them why they could not travel to be with him in his last days of life.

When he finished high school, his high athletic level allowed him to obtain a scholarship to study at the University of North Florida. They had to register him as an "international student”, this meant that his scholarship was three times higher than that of any student, even though he had lived his entire life in the state. The situation would have been an irrelevant piece of information if it weren't for the fact that the coach decided to cut his scholarship a year later, arguing that the resources that the university invested in him could be better used by three other resident students.

It was then that Adrián looked for other options and the University of Saint Thomas offered him a spot. There, Adrián studied Communication with a scholarship, while holding the first place within the tennis team and continuing to compete at college level. But after graduating, the problems returned.

Although he had a degree, he was unable to work on anything related to his career. It was 2011 and DACA was not yet in effect. He spent the next three years teaching tennis informally, assisted by coaches who had known him since he was a boy in Miami.

When the DACA program was announced, it took more than a year to submit his application out of fear. He was concerned that giving authorities so much information about himself would make him too visible a target for deportation. In retrospect, he has no doubt that applying was the right decision: “DACA changed my life… without DACA I would no longer be in this country, I was really already very frustrated. DACA gave me a break and let me know what it is like to really live here”, he says with relief.

Once with his work permit in hand, he returned to college to continue his education, and landed a job as a coach at one of the best tennis clubs in the state, at the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables. In addition, he signed up to be a hitting partner (a high-level player who helps the pros practice before their matches). He did it several times at the Miami Open, at the Cincinnati tournament and at the U.S. Open. In 2017, he helped practice Roger Federer for the Miami Open final against Rafael Nadal.

Today Adrián holds a master in Communications, and has lived in California for a year. He works for a civil organization producing content and developing narratives, where he also advises Hollywood producers and scriptwriters on how migrants can best be represented. He has not stopped giving tennis lessons sporadically and dreams in the future of being able to mix his career with his passion.

-

DACA to become an entrepreneur

By Fernanda Caso

When Maritza and her older sister organized their "quinceañera" party, everything went wrong. The decorations, the choreography, the room and the music were totally different from what they and their parents had chosen. The experience helped Maritza to realize that the event organizers in her city did not realize how much this event meant for families like hers.

Soon after, a cousin asked her for help and she immediately signed up to help her. Things turned out so well that very soon acquaintances and strangers began looking for her to ask her to organize their daughters' quinceañeras.

Maritza had learned to dance self-taught since she was 7 years old. With a K-Paz de la Sierra CD from her brother, she began to practice the steps until she had the choreography of all the songs on the album memorized. In a short time she also learned to dance bachata and cumbia, and took advantage of each family event to practice her steps. When the Quinceañeras came, in addition to organizing their event, she was in charge of the choreography of their dances.

This was not common in her county, Middleton, Wisconsin, where 92% of the population is white and less than 3% are Hispanic. At home and among her parents' friends, Maritza danced and spoke Spanish, but outside of her tight community, she lived like a regular American. She arrived in the United States when he was only 1 and a half years old and she no longer remembers Cholula, Puebla, the place where she was born. She was always proud of her roots, but she knew the importance of integrating into the country where they now live.

In high school, as soon as she was able to get DACA, she took her first job at a fast food restaurant. At the same time, she was involved in clubs, sports and volunteering that could help her improve her profile to obtain a scholarship at the university. Children of undocumented migrants have very little chance of accessing financial support, and those with DACA compete with each other for the few resources that are available.

In her first year of college, Maritza didn't get the scholarship she was looking for. This forced her to take 4 part-time jobs to complete the money she needed. The second year she applied again and had more luck. Because of this, she was able to stop working and focus full time on school. It was then that she decided that she was going to be a businesswoman. She wanted to have enough money to support young people who wanted to study like her. She then chose to pursue a business degree and transform what was once her hobby into a formal job.

Today Maritza is undertaking in the organization of events. Although Hispanics are few in her city, it is a growing population in the state of Wisconsin and there is a large community within 15 minutes of where she lives. More and more families need help organizing quinceañeras and weddings with quality services at reasonable prices. “I saw many parents suffer nervous breakdowns due to the stress involved in paying for parties of this size,” says Maritza. She wants to be a businesswoman with a social sense and that her business serves to create jobs.

-

DACA to become a chef

By Fernanda Caso

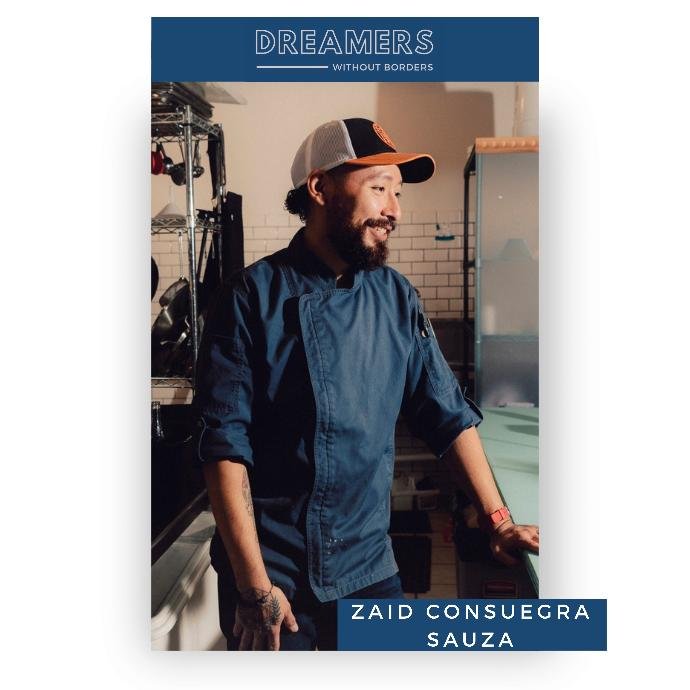

Zaid came to the United States at age 11 with her mother and siblings with the promise that he would be able to return to Mexico to live with his father when he had learned English. The promise was fulfilled and after studying for a year in Kansas City, Zaid returned to Mexico City. The return was not what he expected. He spent most of his time alone and missed his family. It took him less than a month to get back to his mother.

He preferred to be around her, but not that he enjoyed the life they led. Zaid describes his childhood as a "hole" in which all his memories are mixed with work. He spent his afternoons after school in the pizzeria where his mother worked and, later, with his brothers in the store of Mexican products that they opened. They didn't have a lot of money. In reality, they were barely surviving. With the opening of the store, the situation began to improve. They were able to start celebrating birthdays and stop picking up clothes at the Good Will depots every Christmas with their aunt.

But the store didn't last long either. When Zaid began to get excited about the possibility of a college degree, the store went bankrupt and his mother couldn't take the pressure anymore. Seeing his mother burst into tears, Zaid decided to take charge of the problem. He borrowed money from everyone he knew and, without having any experience, opened a restaurant in the same place where his mother had run her business. Somehow, they had to keep paying the rent.

It was at that moment that Zaid discovered his talent in the kitchen. He imagined the saucers and then made them come true. He had never cooked before but had a natural gift for mixing flavors for a creative and engaging menu. Derived from the success, soon after with DACA he was able to get financing from a client to open a cafe. With $2,000 he set up the business and began to experiment. The success was repeated and one year after opening, the cafeteria was already at the top of the city's catalogs.

It was during those years that Zaid became more interested in food and its origin. The more he got informed, the more he became convinced that he should become a vegetarian for reasons related to animal abuse, the environment, and health. He stopped eating meat and then chicken and fish. He finally went vegan. Sometimes he made bagels while he was in the cafeteria to eat while he worked, until customers started asking him to make some for them as well. And from bagels, he moved on to beet burgers.

It was a small business and hamburgers soon became his biggest source of income. It was then that he and his partner decided to close the cafeteria and embarked on a greater adventure. They invested all their savings and spent months of hardship getting financing. They rented a place on the main street of the city, bought all the kitchen equipment, designed a restaurant to their liking and by the beginning of 2019, they opened Pirate's Bone Burguers, a 100% vegan burger and food restaurant. In the first 3 months, his restaurant managed to sell 100,000 dollars, says the chef with pride.

The pandemic has been a severe blow to their business, but Zaid is determined to keep it going. In spite of everything, he does not lose his focus and sense of humor: “I am doing it for all the migrants who come after me. I want them to say: if that guy could, how could I not do it? "

Zaid has been named one of the 9 "rising stars" of Kansas City and his restaurant has been reviewed by multiple local media and Bon Appétit magazine.

-

DACA to promote children’s health

By Fernando Caso

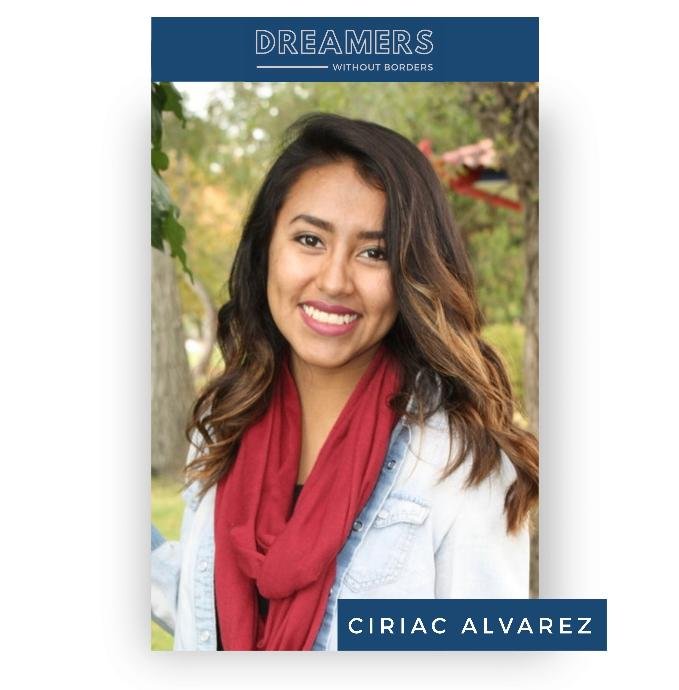

Is Spanish okay? - I ask as soon as we start the interview. Yes, of course- Ciriac responds without hesitating for a second. I realize that, up to now, all of our electronic communication had been in English. A language which, of course, she handles much better than me. Like thousands of Dreamers, she moves between languages with the ease of someone who feels like the daughter of both worlds. Ciriac is.

She was born in Mexico, in the City of Cuernavaca, Morelos and migrated to the United States when she was just 5 years old. She tells the story almost by heart, as if from telling it so many in forums, events and government forums, that person of whom she speaks had detached herself and taken on an independent life. Yes, she is the same little girl who migrated accompanying her parents but, since then, twenty years have passed and she has a built a life in the United States, immersed in its culture, in its school system and among citizens who accepted her as one of their own.

Today Ciriac is a successful professional graduated from the University of Utah and works as a public policy analyst focused on children's health at the Voices for Utah Children organization. Her job is a reality that would have been unimaginable for her parents, who managed to raise her and her two brothers with great effort. Her mother, cooking and cleaning in nursing homes; her father, operating construction machinery.

Ciriac always knew she was undocumented, but it wasn't until she got her first driving license that she felt ashamed. Instead of having a traditional license, she received a credential with the word “Privilege” marked on the front. She preferred not to show it to avoid her friends finding out that she was undocumented. When she entered college, she could not apply for scholarships or jobs that would help her pay for her studies.

When DACA was approved, the possibilities multiplied for her and her siblings. After spending weeks getting all the documents they needed to prove their years in the country (school certificates, bank accounts, proof of address) the three of them applied immediately. A few months later, Ciriac was able to quit her job as a waitress and find employment as a full-time laboratory assistant. Thanks to that, she was able to finish her studies in Sociology and Political Science.

Shortly after, she decided to return to the path she had started as an activist. She first worked in the Mexican consulate, from there she obtained an internship in the United Communities organization helping migrant families, and finally landed a job in Voices of Utah Children, where she is today.

Her days at work go from hours reviewing legal documents to being on the street doing community work. One day she can be promoting the registration of children in the health system among Mormon families and the next day she can be in front of a legislator, explaining the economic impact of a measure that they intend to pass.

For Ciriac, this is just the beginning. The next step for her is to study Public Policy at Princeton or Law at Georgetown. But to plan, you need certainty. “We need a permanent solution, DACA is a program that they are trying to remove at any moment and that is not a way of life. We cannot live with permits that are extended from two years to two years”, she tells me between the serious analyst tone that she practices in her work and a hint of frustration that escapes her... that of the young woman who experiences the consequences of the government decisions tangibly in her daily life.

-

DACA to do digital activism

By Fernanda Caso

Juan ran downstairs after finishing a call with the college he had applied to. He was admitted, but could not enroll if he did not have a Green Card. His mother was frozen when she heard the news in the voice of her son, Juan did not understand and asked her to explain what it meant. Without saying a word, his mother headed for the car. Moments later they were in the admissions office at Florida International University. They were informed that the cost of tuition for them was three times that of any other student in the state for not being legal residents. His mother collapsed in the middle of the office while Juan comforted her and helped calm her crying. For the first time, they realized the limitations that he and his brothers would face throughout life. For now, they had no money to pay for their studies.

The following weeks Juan dedicated himself to researching what this meant. He had promised his mother that he would get into college, and he did. He found a community college that accepted him and from that moment, at age 17, he became an activist. He did it between classes and the job he took to pay for his studies. He didn't have much time available, so he learned digital strategies to do so.

By 2012, his activism had impacted such much, that when President Obama approved the launch of DACA, Juan received a direct call from the White House to announce the news. Juan couldn't believe it, he had already had so many disappointments that it took him a long time to realize that this time it was something real.

“I've been doing this for so long that I saw the so-called DREAM Act tried in 2007 and failed, tried in 2010 and failed, tried in 2013 and failed. I've seen countless immigration reform initiatives come and go, so I'm kind of old when we talk about my longevity within this movement”, he tells me.

Although today, Juan has a career in Political Science and a Master's in Public Administration from Florida State University, he has not given up the fight. He knows that DACA is a temporary and flimsy program, and he also knows that there are many migrants who live in terror every day of the possibility of deportation. Now he doesn't do it in her spare time between busy schedules, today his work as an activist is full time.

Juan Escalante is director of digital campaigns at FWD U.S., an organization that seeks to restore immigration and criminal justice systems.

-

DACA to become a teacher

By Fernanda Caso

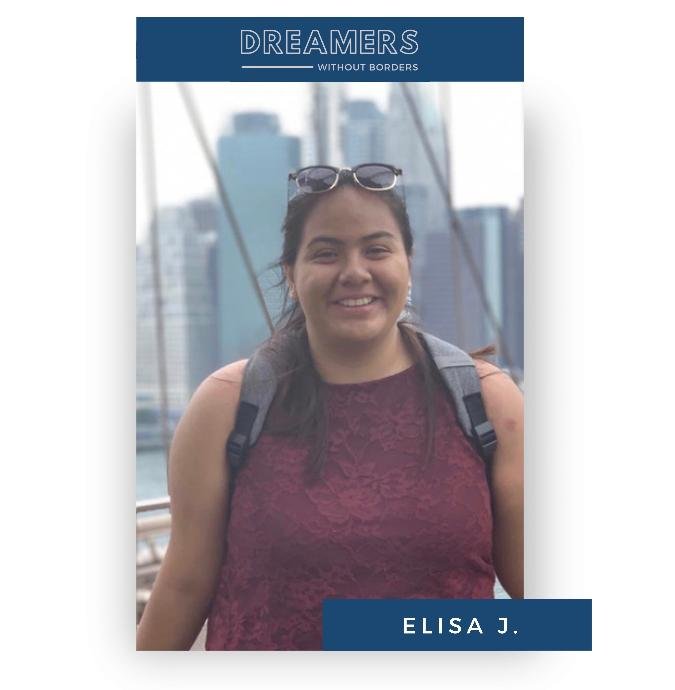

As soon as she turned 15, Elisa signed up for DACA. Her urgency at the time was not yet about the pressure to get into college or get a job. Instead, she had been waiting months to enroll in the volunteer program at LaGrange AMITA Hospital in Chicago, for which she was asked for a social security number. For six years she was helping to transport stretchers, supporting doctors and nurses with supplies and other day-to-day tasks. She always knew that she wanted to dedicate her life to doing something for her community. Her work in those intensive care rooms confirmed it.

But to do it professionally, you needed an education, and in the United States, studying is expensive. Although Illinois is one of nineteen states where the laws allow those with DACA to pay tuition at the same rate as residents, the expense was still sizable and could not be covered by her family.

She got into biology at DuPage College. To do so and stay as a volunteer at the hospital, Elisa had to start taking jobs that did pay. First at a McDonalds, then as a swim instructor, then as a cashier at a family business and at Target. In the moments of greatest crisis, she had to take two jobs to support herself. The pressure led her to neglect her studies and even to reconsider her vocation.

It wasn't until she was invited to a minority health professions program organized by the University of Iowa that her priorities were turned upside down. Elisa recounts this moment as a watershed in her life. The talks they gave there and the people she met were the motivation she needed to keep going. Having already managed to transfer to the University of Southern Illinois, Elisa decided to fully commit to her education to achieve what she dreamed of: being a biology teacher at a public high school to support young people seeking a career in science.

Today Elisa does not imagine herself in a hospital but in a classroom. For disadvantaged children like her, it is only possible to get ahead with the support of a state apparatus that cares about their development. Her own experience is an example of this. Even before the program in Iowa, Elisa has personally seen the difference that committed teachers can make on a student. Since she came to the United States from Michoacán, while in preschool, the school assigned her an English tutor to help her with the integration process. Later, in 5th grade, another Mexican boy came to her school and Elisa was impressed to see how her teacher learned to speak Spanish just so she could communicate with him. Teachers marked her and now she wants to make a difference for more students. She knows that young people need teachers who understand them.

Regarding her immigration status, sge has learned not to think too much about the future. She no longer allows fear of deportation, constant paperwork, and government-generated uncertainty to keep her awake. “I’ve learned to live life,” she concludes relaxed and cheerful after telling her story.

-

DACA to build airplanes

By Fernanda Caso

No more than 10 minutes into our interview, Gastón tells me excitedly that he is about to close a commercial transaction that he had been looking for a long time. He is about to buy a second company to expand his production capacity, his network of clients and, above all, to be able to obtain certificates that allow his company to produce parts for fire trucks in the city of Miami and for commercial aircraft.

Gastón is 33 years old today and is a co-owner of Exclusive Metal Finishing Corp., a galvanizing company that he started almost ten years ago with a friend in Florida. Today they have 7 employees and produce parts for yachts, collector cars, private jets and laboratory equipment. Gastón says that through intermediaries for which he is a supplier, he was able to make some parts for Marc Anthony's plane and all the interiors for Enrique Iglesias's plane. In addition, he has produced parts for airplanes for the governments of Kazakhstan, Colombia and Argentina. The company that he will buy in these days is called Melimar and it has another 5 employees so his workforce would increase to 12 people in a few weeks.

Getting to where he is was not easy. Gastón was brought to the United States by his parents in 2002, when he was 15 years old. He did not speak English well and school was never his strong suit. He started working even before he finished high school and not really knowing what opportunities he would have in the future. He spent his days polishing metals, cutting wood, and assembling materials. In addition to his job, he took other assignments on his own. In seasons he worked up to 17 hours a day.

At the age of 24, he decided to open his own business. Gastón has a charisma and natural intelligence that have opened doors for him, but he acknowledges that he would not have been able to achieve any of this if it weren't for DACA. Many of his clients are in seaports and airports that he could not enter without papers. Nor could he dream of his company being a government supplier.

However, the limitations of the program continue to pose a problem for him. Although today he is a successful businessman, has a home of his own and his son goes to a private school, both he and his wife are still considered illegal migrants. They both DACA recipients and cannot leave the country. Gastón would like to be able to travel to other countries to know and also to grow his business, but his immigration status does not allow it. He and his wife have settled for traveling as much as they can within the United States: Washington, Las Vegas, Arizona, San Francisco, Hollywood, Puerto Rico, Philadelphia and New York are some of the newer destinations he mentions.

Although he and his wife dream of obtaining citizenship one day, there is currently no legal mechanism for DACA recipients to begin the naturalization process.

"I live here. (…) I invest all the money here and I want to grow here” he tells me by way of argument. The United States is his country and he lives that way, although his papers say otherwise.

-

DACA to expand the family business

By Fernanda Caso

They are three siblings: Xóchitl, Citlali and José. Xóchitl is the oldest of the three and came to the United States with her brothers and parents when she was just 3 years old. Her parents were teachers in Lolotla, Hidalgo. Her mother was a primary school teacher and her father a high school. However, they decided to migrate.

When they arrived in Houston, they lived in a duplex and shared the space with four other adults. Her parents started their new life cleaning offices. Later, her father got a job as an electrician apprentice and he devoted the following years to that. Finally, he decided to open his own company.

As for Xóchitl, she was preparing to be a professional boxer while studying high school. She was a very good athlete, but when she started high school her mother warned her that she had to decide what she wanted to do and focus her efforts there. “If you are going to do something, do it well. If not, you better not do it,” she repeated. Xóchitl knew that her parents had come to the United States so that they could have a better education, so she decided to retire from boxing and focus fully on school.

Xóchitl did not know that she was undocumented. She knew she was Mexican but did not have the details of her immigration status. It wasn't until she tried applying to colleges that her mother revealed that she didn't have a social security number. The news affected her greatly. "It is a difficult age in which you are forming your identity" - she says when she remembers that moment. Two years before she had stopped boxing thinking about her studies and now it seemed that she could not do that either.

After doing her research, she discovered that she could apply for DACA and her landscape completely changed. She had studied at a high school that allowed her to start college at the same time. Thanks to this and the fact that she already had papers, she was able to enter LAMAR University and later transfer to Texas Southern University to study Business Administration. She wanted to be able to help her father in the family business.

Today she handles all the paperwork, bank accounts, and splits sales with her father. Her mother handles the material and the accounting. They have 8 employees and are preparing to expand the company. DACA allowed Xóchitl to constitute an L.L.C. and thus get access to government contracts and various sources of financing that until now it had been impossible for them to request.

Did you ever imagine this when you were a girl? - "I am proud that we started with nothing and were able to create something stable and concrete."

-

DACA to be a teacher

By Fernanda Caso

Rafael speaks Spanish, English and a little Zapotec. He has lived in the United States since he was 2 years old and describes his community in Madison, Wisconsin, as an extension of Tanetze de Zaragoza, in Oaxaca, where he and his family are originally from. Over time, many people from his town have emigrated and settled there, more than 3,800 km from their homeland, but close to each other and forming a community. They celebrate birthdays, weddings and September 15 in the traditional style and, as in Tanetze, they organize the feast of the Virgen del Rosario every year. Also, Rafael and his father play together at a mariachi band. He plays the trumpet and guitar, his father the guitarrón.

His grandparents are farmers and his parents were too before they migrated. However, his father had always sought a different life. At some point he tried to be a priest and spent time in the seminary, but eventually he returned to town and married Rafael's mother. In the year 2000 they decided to travel to the United States, expelled by the poverty conditions derived from the fall in the prices of their products in the international market.

He is thoughtful when discussing his experience as a student in the American public education system. “Interesting” is the word he chooses, and he goes on to explain how difficult it was to match his pride in his indigenous roots with his desire to integrate with others. When he studied elementary school, he started a bilingual program that allowed Hispanic children to be in a special group where they took classes in both languages. This had many advantages, as it allowed these children to study without losing connection with their mother tongue. However, it also created a kind of segregation that would accompany them until they started high school.

Rafael always distinguished himself from the group by his qualifications and performance, so during the following years he was able to enter workshops and classes that many of his Hispanic peers could not access. That allowed him to expand his friendships and his intellectual horizons. Since then, he started to get used to being the only person of color in a group.

Once he finished high school, with DACA and his good grades, he was able to get a job at the Centro Hispano organization and apply to college. However, DACA did not solve the entire problem of his status. In the first place, it did not offer him state residence so he could enroll without problems, but he had to pay two or three times more in tuition than his peers because he was charged the international student fee. Second, DACA did not give him access to the scholarships and supports that his peers had access to, so paying for his studies was even more complicated. Each semester it cost him between $ 16,000 and $ 20,000.

With many efforts, Rafael managed to finish his career in Education. His dream was to be a teacher and that is what he is doing now. At Centro Hispano, he teaches an after-school program for high school youth who want to learn about Latin American history, Chicano and Latino cultures, and social justice.

Rafael is 22 years old and has many plans ahead. Right from the start, he wants to go back to college and continue his training as a teacher. “When I was in elementary, middle and high school, all the teachers I had were American or [white] American, until I got to college, I had my first black teachers. I want to try to change that. I never had that opportunity and I want to ensure that opportunity for other generations. "